Prologue

Oh, Lord – the ground beef.

The image of packaged meat sitting in her family’s refrigerator snapped into Gracyn Doctor’s mind. If she had done her job, it would have been out thawing all day. Then late that night, June 17, 2015, she, three younger sisters and their mother could enjoy a meal together. They would gather around a small table just as they had the evening before when Kaylin, the second-oldest, cooked yellow rice, pan-seared chicken and green beans – her mother’s favorites.

Yet Gracyn, home from college and preoccupied on the first day of her new summer retail job, had forgotten about the ground beef when she left for work that morning. So, in a huff, she called Kaylin and asked her to take it out of the refrigerator and let it thaw, then cook it and mix in the Manwich so that the four girls and their mother would have something to eat after work, basketball practice and Bible study.

The oversight was rare: Gracyn had adjusted to the co-pilot’s seat after her parents’ divorce three years earlier left the family with an absent father and five mouths to feed. Social life proved fleeting; Gracyn’s schedule was booked with trips to her younger sisters’ practices, dance recitals and school. She kept her mom awake as they traversed the Southeast through the night, perpetually en route to another volleyball tournament.

Kaylin called back after 9 p.m. and, in one word, the ground beef lost its grip on the day. One of their mother’s friends had called, Kaylin said. She had mentioned a “commotion” at the church – the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. The church where their mother, DePayne Middleton Doctor, anticipated a certification that night that would make her the African Methodist Episcopal Rev. DePayne Middleton Doctor. The church where she would undoubtedly have stayed for Bible study after the ceremony. The church where at least one of her daughters always accompanied her on Wednesday nights – except for this one.

“Mommy’s not here yet,” Kaylin said.

So Gracyn came home to three sisters who needed their mother. DePayne wasn’t answering her phone. And she didn’t pay for cable or Internet – a choice that ensured the fridge stayed stocked with ground beef and chicken – so the “commotion” was left to bedevil her daughters’ imaginations.

Around 11 p.m., the condo’s phone sounded. Gracyn answered – the kind, creaky drawl on the other line belonged to their grandfather, Leroy Middleton. He had a television. He knew something about the commotion. Where was his daughter?

Oh, Lord – the ground beef.

The image of packaged meat sitting in her family’s refrigerator snapped into Gracyn Doctor’s mind. If she had done her job, it would have been out thawing all day. Then late that night, June 17, 2015, she, three younger sisters and their mother could enjoy a meal together. They would gather around a small table just as they had the evening before when Kaylin, the second-oldest, cooked yellow rice, pan-seared chicken and green beans – her mother’s favorites.

Yet Gracyn, home from college and preoccupied on the first day of her new summer retail job, had forgotten about the ground beef when she left for work that morning. So, in a huff, she called Kaylin and asked her to take it out of the refrigerator and let it thaw, then cook it and mix in the Manwich so that the four girls and their mother would have something to eat after work, basketball practice and Bible study.

The oversight was rare: Gracyn had adjusted to the co-pilot’s seat after her parents’ divorce three years earlier left the family with an absent father and five mouths to feed. Social life proved fleeting; Gracyn’s schedule was booked with trips to her younger sisters’ practices, dance recitals and school. She kept her mom awake as they traversed the Southeast through the night, perpetually en route to another volleyball tournament.

Kaylin called back after 9 p.m. and, in one word, the ground beef lost its grip on the day. One of their mother’s friends had called, Kaylin said. She had mentioned a “commotion” at the church – the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. The church where their mother, DePayne Middleton Doctor, anticipated a certification that night that would make her the African Methodist Episcopal Rev. DePayne Middleton Doctor. The church where she would undoubtedly have stayed for Bible study after the ceremony. The church where at least one of her daughters always accompanied her on Wednesday nights – except for this one.

“Mommy’s not here yet,” Kaylin said.

So Gracyn came home to three sisters who needed their mother. DePayne wasn’t answering her phone. And she didn’t pay for cable or Internet – a choice that ensured the fridge stayed stocked with ground beef and chicken – so the “commotion” was left to bedevil her daughters’ imaginations.

Around 11 p.m., the condo’s phone sounded. Gracyn answered – the kind, creaky drawl on the other line belonged to their grandfather, Leroy Middleton. He had a television. He knew something about the commotion. Where was his daughter?

“Did she go to that meeting they had at the church?”

“Yeah, she went.”

“Oh, Lord.”

DePayne Middleton Doctor and her daughters were best friends, occasionally escaping busy lives for the beach. Submitted by Gracyn Doctor

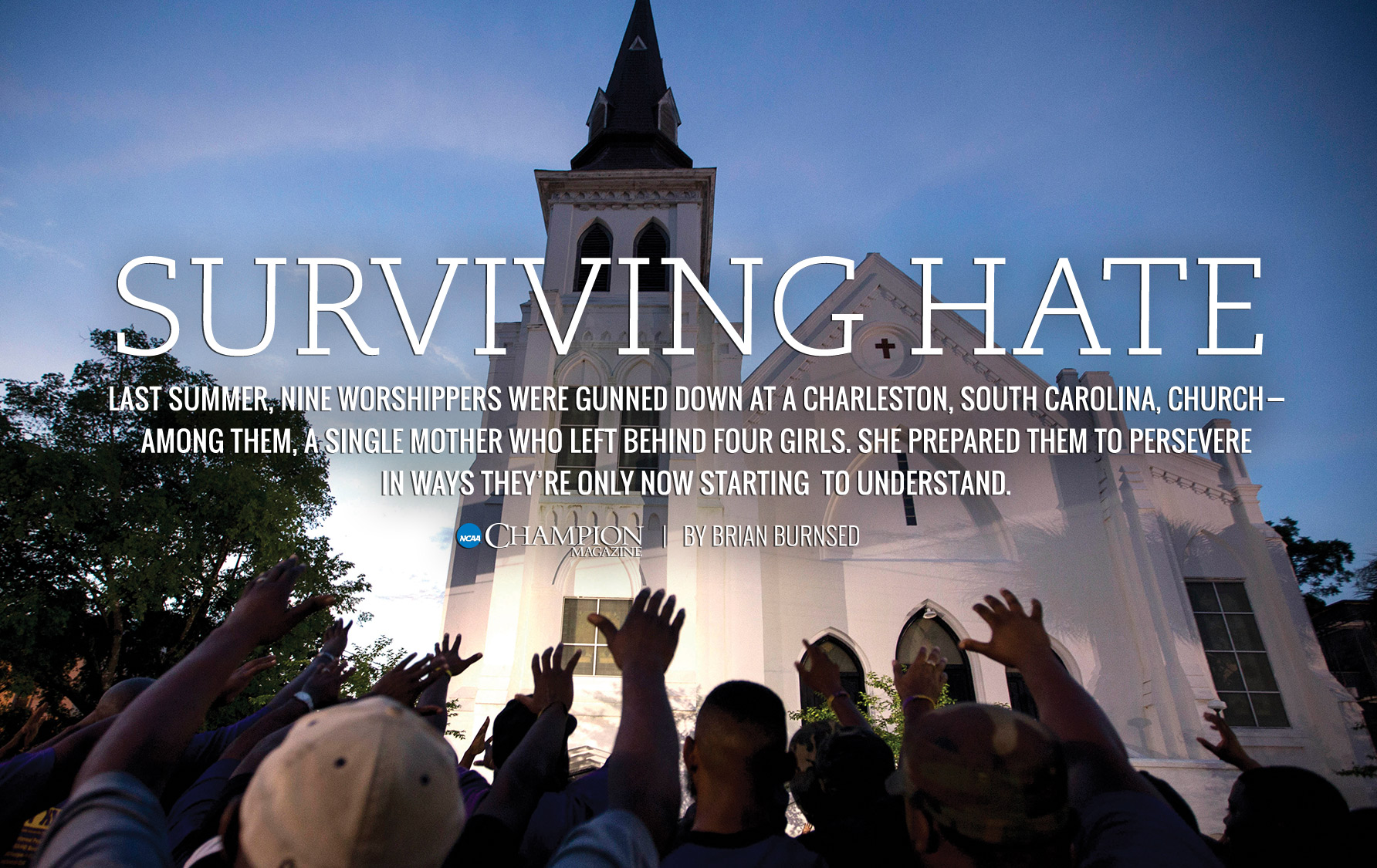

At 9:05 that night, almost two hours before Middleton was dismayed to hear his granddaughter’s voice on the phone instead of his daughter’s, a Charleston 911 operator received a call from inside the church: There was a gun, a shooter – he’s reloading. How many shots fired?

“So many,” the caller said. “So many people dead, I think.”

Around that time, DePayne had been sitting in a plastic chair around a plastic table studying Scripture in the church basement, where the yellowing tiles on the low ceiling hung over wood-paneled walls. On them sat a commandment condemning killing and a prayer beckoning God to deliver them from evil. Nine were murdered in that basement, all black. Each was shot multiple times, allegedly by a scrawny white stranger in a gray long-sleeved shirt with a bowl haircut. He carried a .45-caliber Glock pistol, eight magazines loaded with hollow-point bullets and a heart seeping hatred.

Before the pistol emerged from his fanny pack, those nine – and five survivors – welcomed the stranger through a wooden door on the side of the building that led to the basement. Members of that regal old church in downtown Charleston had done the same for DePayne and her girls seven months earlier. After years worshiping at a Baptist church, Leroy Middleton’s daughter wanted to follow in his footsteps and become an African Methodist Episcopal minister. She reached that goal June 17. About an hour later, she died.

That night, Gracyn was a few months away from embarking on her senior year at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina, volleyball and academic scholarships in hand, and Kaylin had verbally committed to enroll and play volleyball at nearby Johnson & Wales University-Charlotte. Neither daughter has deviated from her path, though each day leaves bruises.

They have not succumbed to the hate the killer had hoped to breed. They have not given in to the grief of having their mother torn from them in a national tragedy. They have not abandoned their school or their sport or themselves. A mother’s sacrifices – devoting untold energy to steering her daughters to college and the promise that lies beyond – ensured they could face the world without her.

Says DePayne’s younger sister, Bethane Middleton-Brown: “She prepared those girls.”

Hali (from left), Kaylin, Czana, DePayne and Gracyn Doctor celebrate Kaylin’s 2015 high school graduation. Submitted by Gracyn Doctor

Procrastination was scarce under DePayne’s roof. The mother of four played volleyball in college, went on to earn a master’s degree and, after a divorce in 2012, supported four girls on a college admissions coordinator’s salary. So if her daughters committed to something, she insisted there would be no half-measures.

For 23-year-old Gracyn and 18-year-old Kaylin, the passion was volleyball. Hali, 13, was drawn to basketball, while her 11-year-old sister, Czana, dedicated herself to dance. As teenage apathy arrived, DePayne preached the importance of commitment. Her lessons came not through a raised voice, but with a packed car after a long workweek as the family drove to another city for another tournament. In the car, DePayne didn’t gripe or let fatigue breed resentment. She instead talked and laughed with her girls on the trips to Alabama, Atlanta or Columbia, South Carolina. “The little stuff, it was a lot,” Gracyn says. “It meant a lot.”

DePayne’s voice was their bedrock. It bellowed from the stands and sang throughout the two-bedroom condo the five Doctor women shared in a Charleston suburb. She sang in their church’s choir – even recorded an album. She made her daughters proud.

On the night of Gracyn’s senior prom, DePayne surprised her daughter with a PT Cruiser, a car of her own. But Gracyn didn’t use it to escape. Instead, she used it to shuttle Kaylin to volleyball, Hali to basketball or Czana to dance. The girls relied on one another through hectic days and savored their family meals around a small table in their condo.

So it was unusual that Kaylin didn’t run downstairs to tell her mom she loved her when DePayne swung home after work June 17 and idled below. DePayne called for Hali to bring her Bible to the car. Kaylin almost joined but was wary of getting roped into the evening’s Bible study. “I do wish that I went down,” she says now. “I really do.”

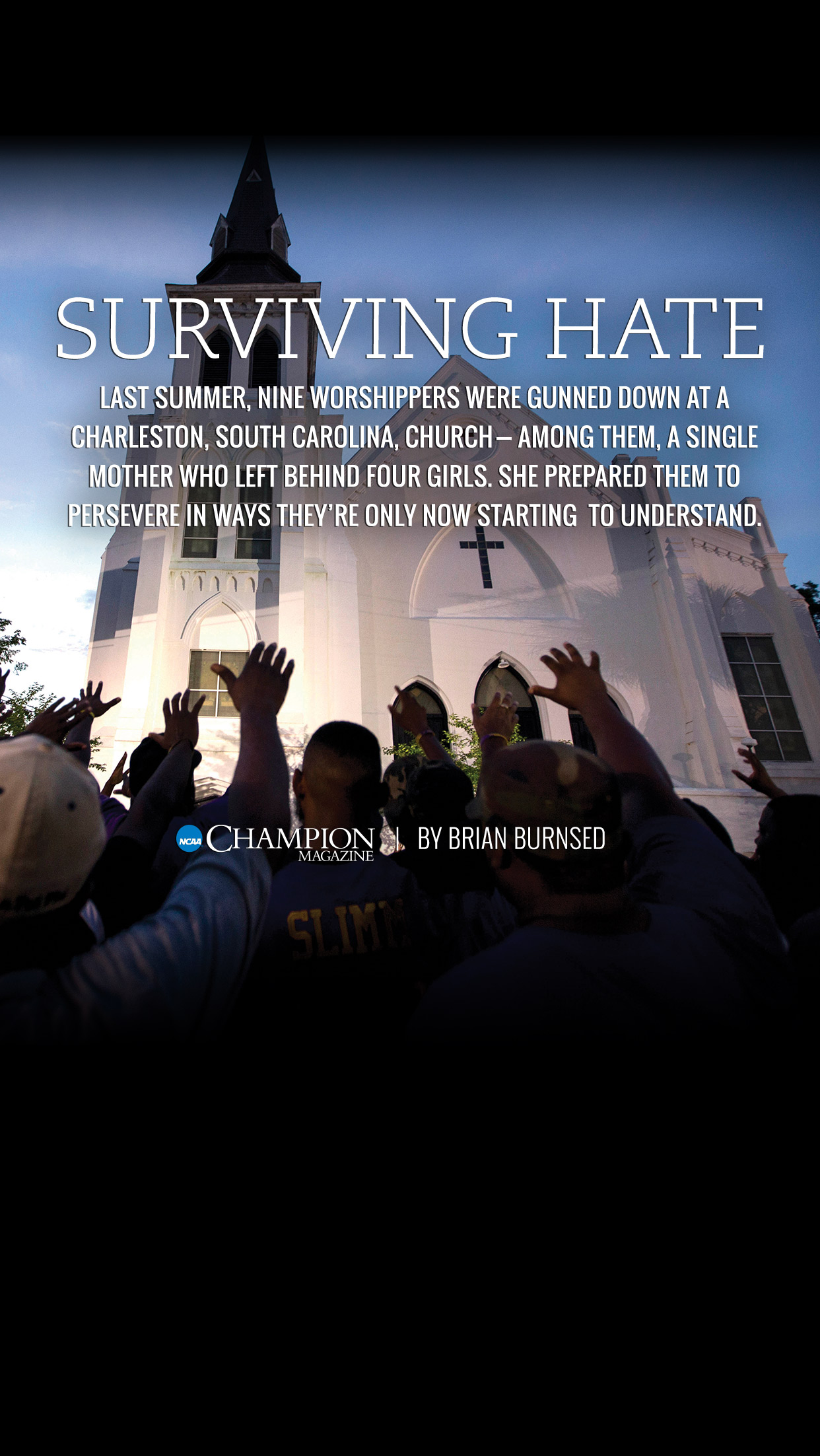

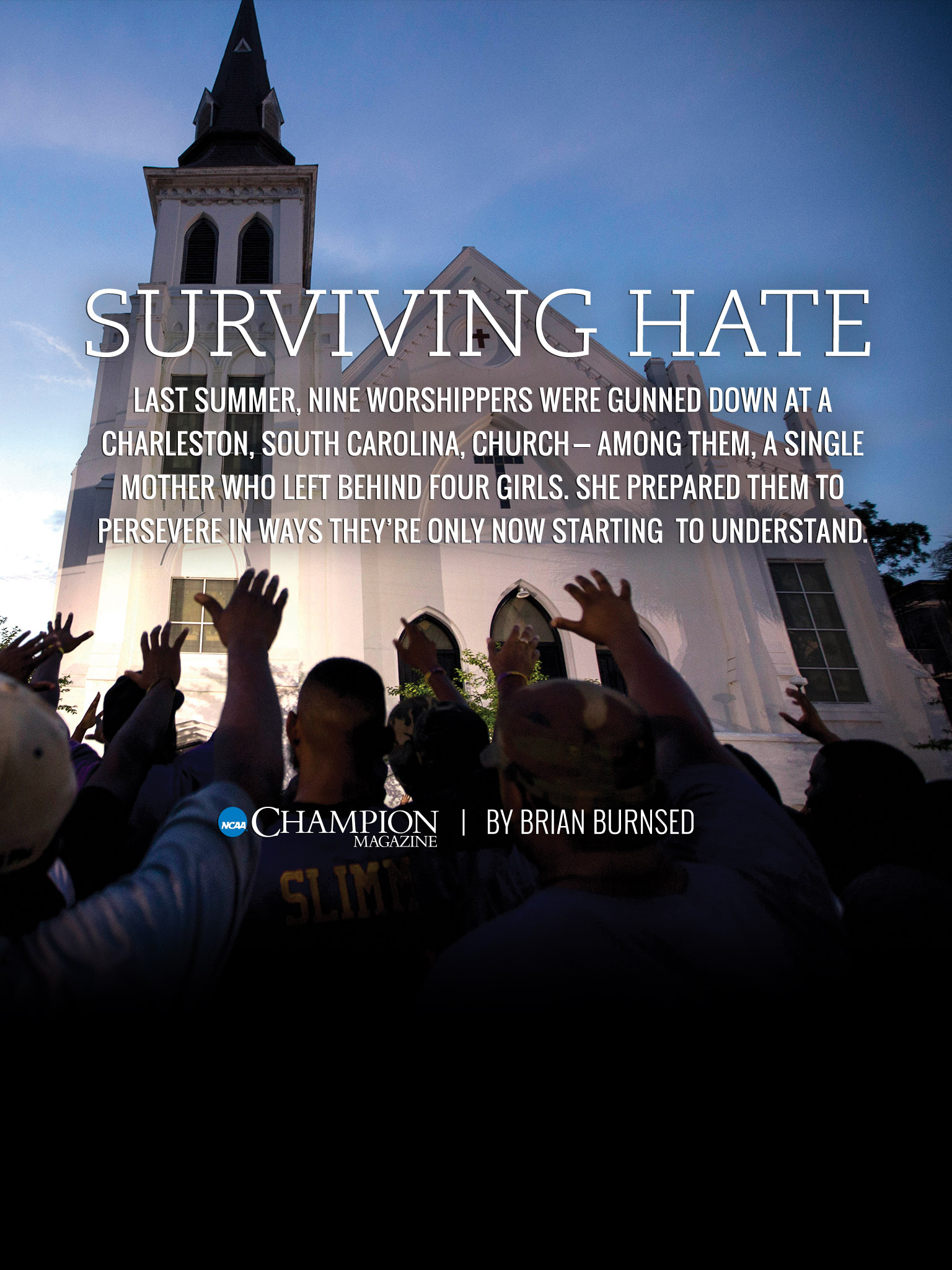

A day after the shooting, a slew of mourners flock to a sidewalk memorial outside the Emanuel Church to hold vigil for DePayne and the other victims. David Goldman / AP Images

That night, after her grandfather’s call, Gracyn dashed to the condo complex’s business office. Each update from local news sites sharpened the terror:

First: A shooting happened near the church.

Then: A shooting happened in the church.

Finally: At least eight people are dead.

Gracyn retreated to a rocking chair outside the office, swaying in the humid night air and thinking about a phone call during a break at work that day – the last time she spoke to her mother. Every day, Gracyn’s phone comforted her on walks to class or on lonely drives, her mother on the other line. On this day, DePayne wished her luck and told Gracyn she couldn’t wait to hear about her first shift at work. Now, Gracyn didn’t know if she would ever get to tell her. So she rocked in silence for 15 minutes and wondered what she would say to the three girls on the second floor.

She followed the example DePayne set when she told her daughters about the divorce, about losing a job, about losing their home, about having to move in with their grandparents until life settled. Gracyn kept her voice level, even as tears spilled down her cheeks. As always, Kaylin turned inward. Nobody would go into a church and shoot. It was supposed to be a safe place.

“It was like we already knew,” Gracyn says.

Photos of the Charleston shooting victims are held aloft during a June 19, 2015 vigil at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C. Glynn A. Hill / AP Images

DePayne sometimes called Mark Raley to check on Gracyn during her first three years playing for him on Johnson C. Smith’s volleyball team. Gracyn had been quick to snap or bicker with the coach as a freshman, but had since earned the role of captain. So he wasn’t surprised when he watched Gracyn stride into the wake, sisters trailing, on the march to DePayne’s coffin and saw Gracyn composed, a shield for the three girls who followed. “I could only see her mother in her,” Raley says. “She did not break. She did not weep.”

Their mother was a silhouette slipping out the condo’s door the last time Gracyn and Kaylin saw her as they lay on the living room couches, half-awake. The next time they saw DePayne, more than a week later, she was in a coffin wearing a carefully shaped smile. To Gracyn, she looked beautiful, but altered. No one told her where the bullets struck. “I can tell maybe,” she says, “because of...” Her voice disappears as she motions to her own cheek, patting it softly.

“I just could tell.”

DePayne wore a white dress and blazer with white pearls that her four daughters, together, selected for her. They spent a day at Belk rifling through dresses, pantsuits and jewelry, mulling the last outfit their mother would wear.

They went on other grim errands. Gracyn picked up DePayne’s Chevy Traverse from the lot behind the church. Gracyn and Kaylin set a date for DePayne’s funeral in the same basement where she lost her life. Neither noticed where the bullets had torn through the ceiling tiles.

People line up to attend the wake of Clementa Pinckney, one of the nine killed in the shooting, on June 25, 2015. The scene at the church was similar when DePayne was laid to rest three days later. David Goldman / AP Images

On June 28, the day of DePayne’s funeral, Callie Phillips stood among the hundreds of mourners who gathered outside the Emanuel Church. Phillips, the volleyball coach at Johnson & Wales-Charlotte, met DePayne once when she accompanied Kaylin on a campus visit almost two months earlier. Phillips sensed the affection DePayne held for her daughter when she probed Phillips. What were the coach’s takeaways from Kaylin’s recruiting video? Phillips told her Kaylin knew how to set up teammates; she frequently made smart plays. “You know my daughter,” DePayne said.

Kaylin verbally committed soon after with her mother’s blessing. DePayne died two weeks later. Eleven days after the shooting, Phillips found herself in line next to Raley, Gracyn’s coach, outside a church in Charleston. There, a white man allegedly murdered nine people because they were black. Phillips felt “almost ashamed to be a white person in that setting,” but Raley had reassured that her presence would help. So she joined Raley and more than 30 other students, teammates, coaches and administrators from Johnson C. Smith to pay respects to the gracious woman she met months before.

Temperatures soared past 90 as women in black dresses took off high heels to rest weary feet. Red Cross workers handed out water. Photographers snapped pictures from rooftops. Kaylin took note amid the relative chaos of the signs telling her and her sisters how much they were loved. She was heartened: There had been no riots or violence in her mother’s name.

The girls sat inside the church watching the funeral unfold a day after they shook hands with the president and vice president of the United States. The latter spoke to them through tears and tried to relate to their pain – he had recently lost a son.

The packed crowd surged inside when the church doors opened. Hundreds quickly filled the sanctuary, so Phillips, Raley and the Johnson C. Smith contingent were forced to wait outside. Phillips watched a white man in the street spew bigotry cloaked in Bible verses. He shouted at the masses until a group of black mourners surrounded him and sang “Amazing Grace.” He tried to yell over them; they sang louder. They sang until he stopped screaming and sang when he started screaming again, his words engulfed by the familiar melody.

Phillips listened. Then she wept.

Every day, Kaylin wears her mother’s class ring from Columbia College (South Carolina). Jason E. Miczek photo

Tell the class something interesting about yourself, Kaylin.

Volleyball. The answer always had been volleyball. But when college classes started at Johnson & Wales-Charlotte in the fall, the familiar request stung. Kaylin’s answer changed. She lost her mother in the church shooting in Charleston. Yes, she told the class, that one. Against her will, the volleyball player had been redefined. “I don’t like that to be my interesting fact,” she says.

She sensed the field of eggshells around her when others approached. But she didn’t notice the covert actions her new coach and team took to spare her from undue pain. Before Kaylin arrived for orientation, Phillips panicked. DePayne had signed up to accompany her daughter. Her nametag would be placed on a table. Kaylin would undoubtedly see it, lingering through the day, unclaimed. So Phillips contacted the staff responsible for the event: Replace it, she told them, and make sure a nametag was out for Gracyn, who insisted on playing her mother’s role.

Whenever news about the shooting flickered on the television, teammates distracted Kaylin or changed the channel. Before the team’s first practice, Phillips asked Kaylin where the boundary should be set. Could she tolerate yelling? “Coach, treat me how you would treat me any other way,” Kaylin told her. Volleyball was her outlet. She refused to play on a court of eggshells. When she failed, she demanded the ball come her way again. Redemption soothed better than pity.

Teammate Tiy Gonzalez was one of the few Kaylin permitted to peek inside. Gonzalez appreciated it when, unprompted, the quietest girl on the team began telling stories about how much she missed her mom’s voice. About how she sang in the kitchen or in the car. About how much DePayne appreciated it when Kaylin cooked – the seeds of her decision to become a culinary arts major. She made brown sugar-glazed meatballs for Gonzalez. She hasn’t, however, cooked chicken and rice since her mother’s death.

Gonzalez saw the usually placid Kaylin fume if she misplaced her phone or credit card, if anything of importance in her life slipped out of her control. Some mornings, Kaylin lingered in bed, no strength or will to rise for an early class. For so long, she had been the first sister to waken; now she risked failing classes in what became a perpetual stupor. Her grandparents frequently called to offer counsel. “Don’t put it off because it don’t feel good,” they told her. “Let’s go and get it done.”

Gracyn moved into a campus apartment at Johnson C. Smith, only a mile northwest of Kaylin’s school. Raley and members of the football team helped the girls’ aunt, Bethane Middleton-Brown, and her family move to a larger house in the suburbs, 25 minutes north of downtown Charlotte. With three children of her own, Middleton-Brown needed more room for Hali and Czana to live and for Gracyn and Kaylin to visit every week. So she bought a white two-story house with dark hardwood floors and a fenced backyard where a pair of dachshunds could roam.

A psychotherapist, Middleton-Brown quickly set the girls up with counselors. She connected them with a financial advisor to help manage the money they received from donations and a government payout to the victims’ families. Their aunt saw the sisters snip at each other, and she saw them cry. Mostly, though, she saw them return to school and stay afloat in class and play college volleyball – the fruits of her sister’s devotion to her girls.

At Johnson C. Smith’s first tournament, Raley’s captain wore the face of the volatile freshman he once knew. He grabbed Gracyn’s hand and pulled her aside to decompress. He would do the same during practices throughout the year when the inevitable stress of a murdered mother, a looming trial and young teammates who struggled to empathize reached a boil.

Khadijah Segura, Gracyn’s teammate and former roommate, understood. When they lived together, Gracyn would complain if she and her mother let most of a day slip by without speaking. Segura grew accustomed to hearing Gracyn yapping about the day’s minutiae with her best friend. Gracyn was forced to spend her senior year without those conversations. She confided in Segura before some practices that bringing a team captain’s energy was certain to take a toll. “There’s only so much that somebody can bear,” Segura says.

“If you need anything, just let us know,” friends, administrators and complete strangers told Gracyn and Kaylin throughout the year. The sisters had no idea how to respond. No one could bring back DePayne’s voice for Kaylin or her words for Gracyn. No one could give Kaylin another chance to run downstairs, Bible in hand, and say goodbye.

Gracyn’s teammates at Johnson C. Smith took part in a ceremony before an Oct. 1 game against her sister’s team, Johnson & Wales-Charlotte. Each hugged Kaylin and presented her a rose. The moment brought both sisters to tears on the court. Jonathan Keittk photo

Nine names boomed over the public address system Oct. 1 in Johnson C. Smith’s Brayboy Gymnasium before Gracyn’s team faced Kaylin’s. The athletes wore volleyball shorts and kneepads and held red and white roses. Some bowed their heads.

CYNTHIA MARIE GRAHAM HURD

SUSIE JACKSON

ETHEL LEE LANCE

DEPAYNE MIDDLETON DOCTOR

CLEMENTA C. PINCKNEY

TYWANZA SANDERS

DANIEL SIMMONS

SHARONDA COLEMAN-SINGLETON

MYRA THOMPSON

Candles bearing each name sat in the lobby along with a framed photo of DePayne. Her chin rested in her hands, a silver ring with a black stone – a ring Kaylin now wears every day – graced her finger. DePayne’s wide eyes looked forward.

Gracyn and Kaylin saw the picture before they walked onto the court that night, nearly 800 people in attendance. They came to see two sisters embrace. Visitors made speeches in the name of nonviolence. Then Gracyn and Kaylin stood alone in the middle of the court, 800 pairs of eyes fixed on them.

Kaylin hid from the stares. She buried her face into Gracyn’s right shoulder and wrapped an arm around her waist. They whispered to each other – mom would have been proud – as the voice resonating through the gym assured them that everyone there loved them. But no one could see the loneliness they shared. No one in that gym understood what it meant to be one of the girls whose mother drove them to yet another volleyball tournament every weekend without complaint. A mother who made noodles and cheese in a cramped condo feel special. So, alone together on the court, they hugged tight.

When they separated, Kaylin looked like a child watching her mother walk away on the first day of school – chin scrunched, eyebrows pulling down. So Gracyn placed her right hand on the side of her sister’s face and leaned back in to kiss her cheek.

A decade earlier, Kaylin followed her sister out to the driveway of their small suburban Charleston home. Gracyn often batted the volleyball up to herself, training, and rebuffed Kaylin’s pleas to play. Eventually she capitulated and introduced her younger sister to the sport. From that moment, whenever teachers asked for an interesting fact, Kaylin always had the same answer.

They never squared off in high school or in club matches. Then, despite interest from Division I programs, Kaylin followed her sister to Charlotte like she had onto the driveway. There, the regional rivalry guaranteed they would play against each other. “I won’t know what side to sit on,” DePayne told her daughters after Kaylin committed. Instead, her picture sat on a table in the gym lobby.

Throughout the match, Gracyn frequently targeted Kaylin. Phillips and Raley assumed a sibling rivalry had trickled onto the court as Gracyn pounded the ball at her younger sister and Kaylin leaped and dove, rebuffing the attacks. They didn’t realize that Gracyn simply wanted her sister to have more chances to hit the ball, to get better.

DePayne always had been in the stands whenever Kaylin played despite her obligations to church and work and three other daughters. Her mother was the person whose heart swelled with Kaylin’s successes.

Now, Kaylin says, it’s Gracyn.

DePayne Middleton Doctor’s grave rests in a quiet corner of a cemetery northwest of Charleston. Brian Burnsed / NCAA

Leroy and Frances Middleton gather the mail addressed to their granddaughters from strangers around the country and give it to Gracyn and Kaylin when they visit. In them, the girls find letters of support or prayer shawls or books about recovery and grief. But Kaylin has learned to be wary as she sifts through the envelopes. Some letters are laced with venom and slurs directed at four girls and their dead mother simply because they are black.

Gracyn grows nervous around “rugged” white men; Kaylin avoids any who look “strange” – who look like him. She dreaded entering a Wal-Mart for months for fear of crossing the path of scraggly boys with bowl cuts and lifeless eyes. Gradually, the anxiety erodes. “I just can’t be afraid of anybody,” she says.

Once, a business card bearing a Confederate flag tumbled from an envelope Gracyn opened. She still shakes her head, muscles tense, when she remembers. Gracyn saw those flags throughout her youth; they were emblazoned on the back of the white boys’ trucks in high school. She gave them little thought. Maybe it was their culture? Now she turns the other way if she sees white stars on blue bars. Now she sees a warning. “You just don’t know,” she says.

Gracyn used to feel contentment as she watched the pines give way to palm trees on the three-hour drive to Charleston. Now a grave grows closer, metal and stone laid flat against the earth. She sees a courtroom, where she soon will be forced to share air with the man accused of taking her mother’s life. She has been in the room with him once before – a federal bond hearing last year. Athletic and 6-foot-1, Gracyn wanted to bludgeon him. But she stayed calm and, when presented the chance, addressed the court. “Even though he has taken the most precious thing in my life,” she said, “he will not take my joy.”

Both sisters insist they will go to Dylann Roof’s trial when it begins July 11. Both have avoided news reports offering insight into what occurred the night of the slayings, but Gracyn wants to hear every detail in the courtroom. She can’t be spared what happened because she refuses to let mystery cloud the moment that reshaped her life. She knows it will be difficult when she sees the photos and hears the grim particulars – like peering into her mother’s coffin and spotting a hint of lingering carnage. “If I tried to stop her, I would be wasting my time,” her aunt, Middleton-Brown, says. “It’s going to hurt her.”

Kaylin will go because she wants her identity back. She needs to hear Roof convicted and sentenced. Then, when a teacher asks her to share something interesting about herself, she can say, without pause, that she is a college volleyball player – just like her mother.

The sisters regularly attended church through their youth, listening to their mom’s tenor in the choir. They stay away now. The gospel music, the feel of smooth wooden pews against Sunday dresses – they remind them too much of DePayne. Both feel their own faith strained after the faith of their mother, a woman who insisted on giving time to God on Wednesday nights, and who tithed even when there was no money for cable and Internet, was rewarded with slaughter. It was supposed to be a safe place. “I have so many questions,” Gracyn says, “and I just don’t understand.”

The family continues to wait for the trial and punishment – the state of South Carolina is seeking the death penalty – and whatever closure they may provide. Leroy Middleton, the patriarch, the African Methodist Episcopal minister for decades, points his family to the book he knows best and hopes that, their faith tested, they don’t despair through the long months ahead: Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: “It is mine to avenge; I will repay.”

“That young man,” he says, “is in the hands of the Lord.”

Kaylin (left) and Gracyn each keep a few mementos that remind them of their mother. Sifting through her belongings proved difficult, so family members helped. Jason E. Miczek photo

D ePayne’s name is now peppered throughout Emanuel’s basement: on framed posters honoring the victims; etched into one of nine metal plates affixed to a tall cross that stands near a flat-screen television displaying feeds from 16 security cameras. Older black women in cardigans sit in plastic chairs around plastic tables eating chicken salad and drinking Coca-Cola poured from half-empty 2-liter bottles. They converse quietly a few feet from a smattering of bullet holes in the ceiling tiles. The church’s front doors are locked; so is the side entrance that the gunman entered, though members remain willing to welcome a white stranger into the basement.

Gracyn and Kaylin share a two-bedroom apartment in uptown Charlotte. Though Kaylin hasn’t made chicken and rice since the shooting, she has tackled DePayne’s red velvet cake recipe. Kaylin’s isn’t quite as delicious, but she has years more to learn to match her mother. Gracyn will graduate with honors in May. This semester, she is balancing college classes with an internship at a local television news station, and she rises each day knowing she will face many more hours without DePayne to fill the quiet.

As Gracyn prepares for work every morning, she grabs a rectangular pin bearing DePayne’s image – chin resting in her hands, wide eyes looking forward. Gracyn’s fingers guide the sharp point through the fabric on her lapel and squeeze the metal into its clasp. She closes her eyes and takes a breath, deep and deliberate, before they open. On the pin, three words rest below her mother’s face: “Hate didn’t win.”