The 7-year-old’s epiphany came in the middle of a professional wrestling match.

Carol Hutchins had watched bouts like this before on television: Two well-muscled bodies slamming against one another, contorting into unnatural positions and ricocheting off ropes tethered around the ring. It was the mid-1960s, and the wrestling program was common entertainment in the Hutchins household. But on this day, the young girl noticed something strikingly different about the two wrestlers. Their faces weren’t hairy, and their bodies weren’t half-naked. Their hair wasn’t cut short like her brothers’, but dangled long like hers.

These wrestlers were … women.

Hutchins stared in amazement. Then she knew. “I want to be a lady wrestler,” she told her mother.

In their 37-year study, researchers R. Vivian Acosta and Linda Carpenter tracked the decline in the percentage of female head coaches in 24 women’s varsity sports. Before 1981, when the NCAA began sponsoring women’s sports, numbers were collected from the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women.

Decades later, the declaration still draws laughs. But in that moment, to a 7-year-old Hutchins, it made perfect sense. She had never seen an athlete on television who looked like her. She had never encountered other girls who liked to do “boys stuff” like she did. Maybe her preference for basketballs over baby dolls wasn’t so odd, after all. Her imagination churned.

By high school, Hutchins had outgrown that childhood dream. But the sphere of possibility swelled again when, in the summer of 1973, she joined a club softball team coached by a woman named Kay Purves. Shortly after, Anne Johnson became the coach of Hutchins’ high school basketball team. A self-described tomboy and a dogged athlete, Hutchins had played under many strong, talented male coaches. She just hadn’t seen herself in them – until she met Purves and Johnson.

Just as the female wrestlers had 10 years earlier, the two female coaches who led practices with whistles around their necks and fire in their stares showed Hutchins a world she didn’t know existed — a world she suddenly realized she could join. I want to be a coach, she told herself. And this time, the idea stuck.

These earliest female influences opened the door to one of college sports’ all-time coaching successes. Hutchins is the winningest softball coach in NCAA history. She is heading into her 33rd season as head coach at the University of Michigan, where she is the winningest coach — male or female — in the school’s history, and where she has never experienced a losing season. Her softball program has also propagated even more female coaches: 18 of her former Michigan softball players are now head or assistant coaches at NCAA schools. Dozens of others are former coaches or lead softball programs at the high school or club levels.

What would have happened if Hutchins had never met those two female coaches in high school? Would she have even thought about coaching?

Likely not, she says. “You can’t want to be something there isn’t.”

Michigan’s Carol Hutchins holds 19 regular-season Big Ten titles and one NCAA championship. Daryl Marshke / University of Michigan

1. Ease concerns around child care. Consider assisting with the costs or offering an on-site day care built around the hours of athletics staff. “A lot of universities provide day care services,” says Marlene Bjornsrud, former executive director of the Alliance of Women Coaches, “but they’re built around faculty hours, and we know coaches don’t work 9 to 5.”

2. Encourage coaches to take a break. From family or medical leave to summer vacation, coaches should feel comfortable stepping away. And, particularly for mothers taking maternity leave, they need the personnel support and resources to make it possible. “People should know that it’s not only OK, but that you really should for your own welfare take some time away,” Binghamton University Athletics Director Patrick Elliott says. “I think it has to be a part of the culture.”

3. Open your doors to family members. Accommodate coaches who want to bring their children to practices or away games and invite families to department events, such as holiday parties. “We’re not finding a cure for cancer with what we do,” says Peg Bradley-Doppes, vice chancellor for athletics and recreation at the University of Denver. “The environment should be demanding but fun.”

Hutchins isn’t the only successful female coach with strong female role models in her biography. Pat Summitt played in college under Nadine Gearin, the University of Tennessee at Martin’s first women’s basketball coach. Tara VanDerveer, the standout coach of the Stanford University women’s basketball team, was coached by Bea Gorton at Indiana University, Bloomington. The dominating women’s volleyball coach at the University of Florida, Mary Wise, learned from Carol Dewey, her coach at Purdue University. The list goes on and on.

The pieces came together for Lenika Vazquez early. She gave birth to a son, married and landed a high-profile job in a field she loved by age 25. As a young professional, her life seemed picture-perfect. Except Vazquez found that coaching college volleyball didn’t always mesh with the expectations to which she felt society was holding her.

Yet in 2016, while more women play college sports than ever before, just over 40 percent of NCAA women’s teams have a female head coach. That number is down from 55 percent when Hutchins began her coaching career in 1981 — the year NCAA women’s championships got their start. And, according to the “Women in Intercollegiate Sport” study produced by Brooklyn College professors emerita Linda Carpenter and R. Vivian Acosta, before Title IX — the 1972 federal gender equity law — more than 90 percent of women’s teams were coached by women. The steady decline over the decades begs the question: What is driving women away from coaching?

Broad answers to this question begin to emerge through examination of studies, statistics and headlines — and through interviews with current and former coaches, directors of athletics, conference commissioners, researchers and gender equity advocates. The individual stories venture beyond the numbers to the emotional core of the issue, a place where frustrations and fears and hopes and ideas live. Together, they reveal a mosaic of complex challenges and deterrents faced by female coaches.

“There is not one word or one scenario I can give and say, ‘This is going to help us move forward and get more women to be in coaching,’” says College of Saint Elizabeth Athletics Director Juliene Brazinski Simpson, who coached women’s college basketball for 27 years before transitioning to athletics administration. “I think there’s just a lot of stereotypes that make this a very complicated situation.”

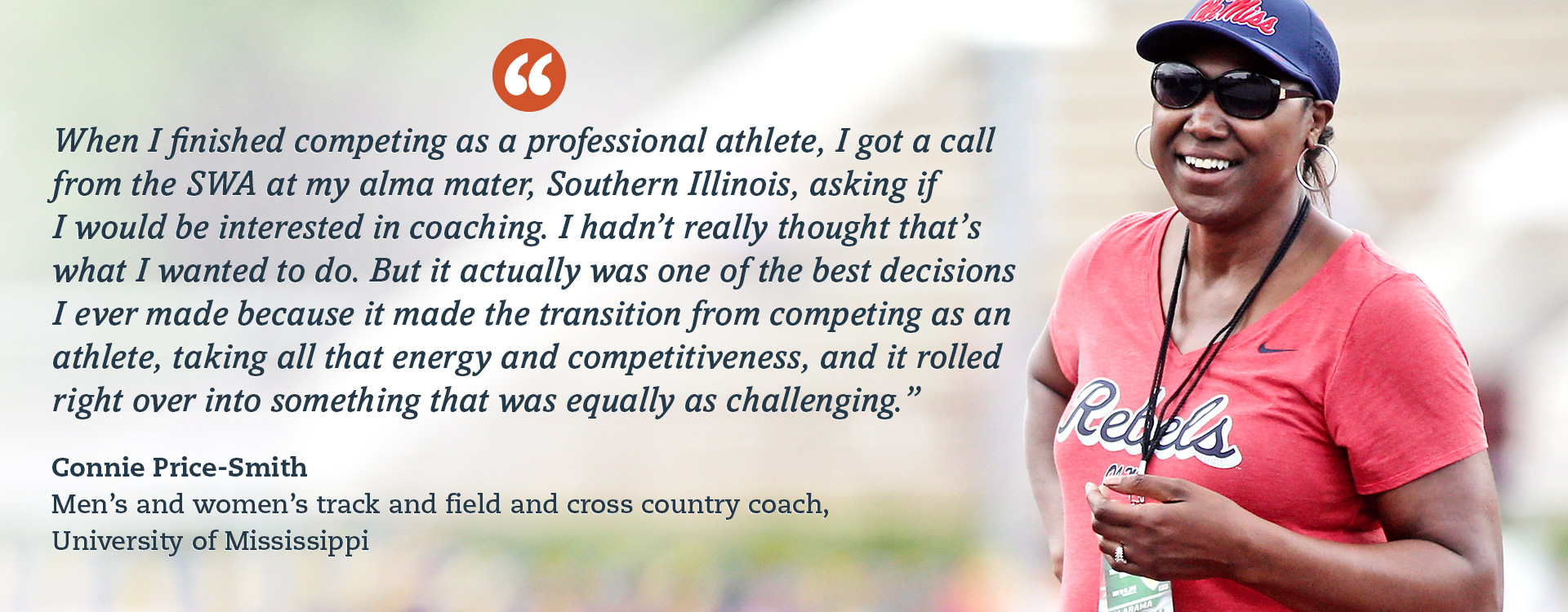

Petre Thomas / University of Mississippi

1. Encourage professional growth opportunities. Julie Soriero, athletics director at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says athletics directors have a responsibility to support professional development for coaches. Provide them with a path to attend coaching conferences or professional trainings.

2. Involve them in the department. “If the female is one of a small number of women in the department, the administration really needs to make sure that individual feels included,” says Judy Sweet, co-chair of the NCAA Gender Equity Task Force and a former membership-elected president of the NCAA. “Invite that individual to lunch, to any social events, so they don’t feel they’re an outsider.”

3. Stay connected. A lot of the responsibility with networking falls on the young person looking to advance, but veteran coaches and administrators can help. “If you find a female that is passionate about being a coach, you just have to make sure you keep a connection with her,” says Juliene Brazinski Simpson, athletics director at the College of Saint Elizabeth and a former women’s college basketball coach. “Help her find her path.”

Simpson chuckles when she remembers a phone call she and her husband received on their way back from the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, where Simpson had just finished her run as co-captain of the U.S. basketball team alongside Pat Summitt. An administrator from a New Mexico high school was searching for an athletics director along with coaches for both women’s basketball and track and field. “How about you become the athletic director and basketball coach,” the man asked her husband, “and Juliene does track and field?”

"In my early 20s, when I coached college tennis, I experienced all kinds of subtle discrimination and harassment. I wish I could have known then what I know now."

Her husband replied with a more logical idea: Juliene would coach basketball, because, after all, she was an Olympian. He would coach track, and they would share the athletics director duties. “That was way back in the ’70s,” Simpson remarks, “and yet we still have that look at hiring.”

Back in the 1970s — that was an era when most women’s teams were helmed by female physical education teachers who stayed after classes to coach for free. When women’s basketball squads were still limited to half-court play. When female student-athletes crammed into cars for road competitions and, sometimes to save cash, slept on the floor of the gym on which they would play the next day.

“I was at an absolute breaking point with how I was living. And not only was I not happy with myself as a wife and a mom, but I wasn’t happy with my growth as a coach. I just had to step back — it was either that or get out.”

Title IX kick-started progress because it required schools to provide equitable opportunities for both male and female student-athletes. The law sparked a proliferation of new varsity women’s teams with more resources and salaried coaches. It also led many schools to combine their men’s and women’s athletics departments — a consolidation that often meant putting one athletics director in charge of it all — typically, a man. Today, only 20 percent of NCAA athletics directors are female, according to NCAA research.

As women’s sports blossomed and coaching positions became more lucrative and prestigious, the jobs grew increasingly attractive to anyone looking for a coaching career, including men. The additional opportunities gave male coaches two avenues to pursue coaching: in men’s sports and in women’s sports. Yet female coaches didn’t experience that same job market expansion across genders, as their chances remained primarily on the women’s side of athletics. Currently, around 3 percent of NCAA men’s teams are helmed by women.

“I look over at the men’s side in sports, and just short of 100 percent of the coaches for men are men,” says California State University, Fullerton, Athletics Director Jim Donovan. “So that’s the culture for men’s sports. I don’t understand why the culture for women’s sports can’t be that women coach and mentor women.”

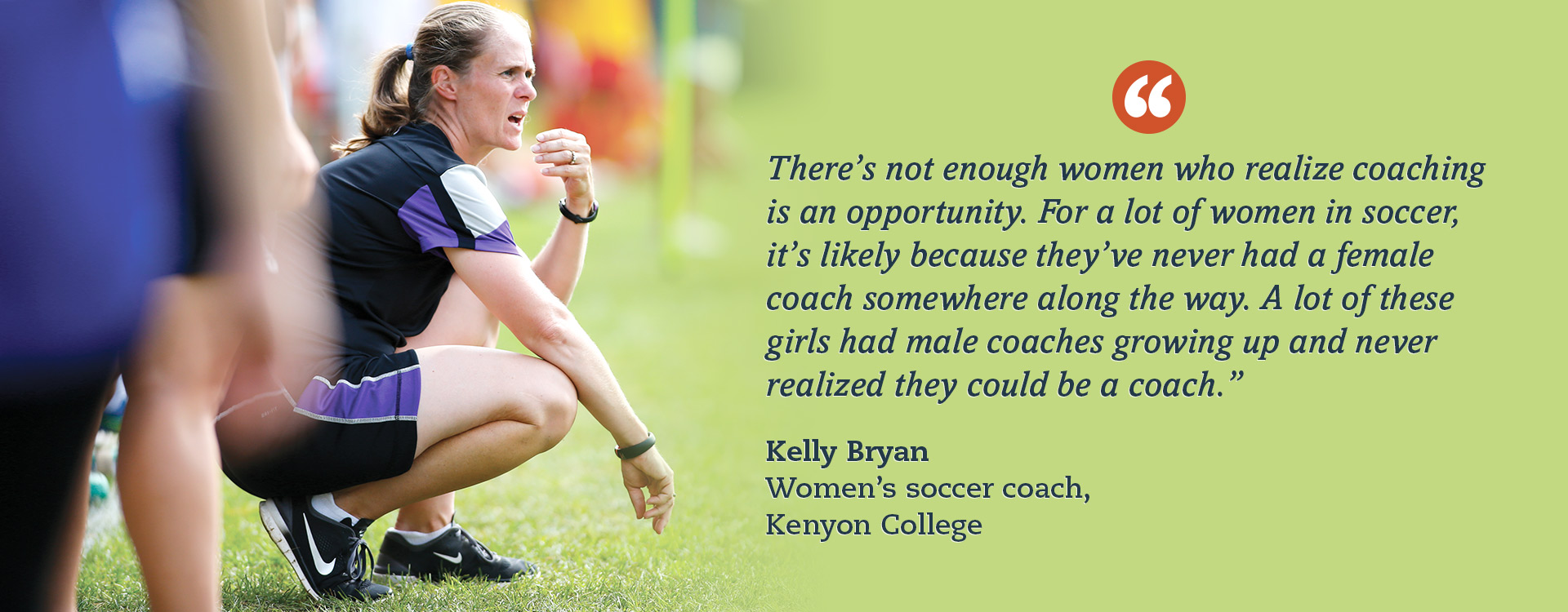

Kenyon College photo

1. Be open with your coaching peers. Share ideas. Talk technique. Ask questions. “As females, we often feel we need to be in a complete trusting relationship to share information,” says Lenika Vazquez, women’s volleyball coach at Canisius College. “Men will often just get together and talk. They don’t need to know their background or be friends. We need to be able to openly share information about what we do, how we got where we are and what makes our program successful.”

2. Check in with your contacts on a regular basis. Drop them a note when you’re in town. Congratulate them when they’ve gotten an award. Stay in touch as you both move along in your careers. “It’s the responsibility of the younger professional to be able to take advantage of maintaining good professional networks,” says Bernadette McGlade, commissioner of the Atlantic 10 Conference. “You never know where people end up in this business.”

3. Get involved with female coaching groups. Organizations like the Alliance of Women Coaches and the National Association of Collegiate Women Athletics Administrators provide opportunities to network and grow, as do trainings like the NCAA Women Coaches Academy. “I would highly encourage other women to explore your options for connecting with other females in your industry,” Commons-DiSalle says.

Leading women in the profession halt assumptions that the opportunities given to their male counterparts are the sole reason for the percentage drop in female coaches. The problems’ roots, they say, are more systemic. In some cases, women aren’t applying for positions. In others, female coaches are leaving the field — willingly or not — long before they’re ready to retire. The trends are a perplexing turn of logic, given a series of other data: More women than ever are playing sports — nearly 212,000 in NCAA championship sports, a 25 percent increase in the past 10 years alone. More coaching positions exist, too, as the number of NCAA women’s teams has risen 14 percent in that same window. And the prospects of building a sustainable career are far greater than the days when women were coaching for free after school.

“Connecting with other females is important, because more often than not, they are going to be so open to helping, to mentoring, to guiding. Likely some of the things that are concerns of yours are the concerns of other females in the industry.”

Female representation among coaches is highest at the most entry level of positions — graduate assistants, volunteer assistants — but drops as the level of the position rises. About half of paid assistant coaches for women’s teams are women, roughly 10 percent higher than the number of head coaches. “As the position becomes more visible and more powerful and more lucrative, we have fewer females,” says Nicole LaVoi, co-director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport and author of the book, “Women in Sports Coaching.” “They’re dropping out of the pipeline. And to me, that’s troubling.”

Conversations with coaches across the country unveil an array of factors: The increasing demands of the job. The strain on working mothers. Fear and discrimination among lesbian coaches. Lack of mentors. Lack of networking opportunities. Perceived gender biases. Marlene Bjornsrud, the former executive director of the Alliance of Women Coaches, discussed these and many other factors at a round table of female sports leaders in 2014. In total, the group identified 28 key reasons women were leaving college coaching. “It’s a fascinating and complex issue that nobody has figured out the answers to,” Bjornsrud says.

When her 14-year tenure as the women’s basketball coach at Vanderbilt University came to an end last spring, Melanie Balcomb reached out to her respected peer Dawn Staley, coach at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. The conversation sparked an idea for a new, unique position in women’s basketball – and in the process, kept one experienced coach in the game.

Don’t try to tell Tonia Walker women aren’t applying. The athletics director at Winston-Salem State University might not believe you, given that she has attracted female head coaches for all six of the university’s women’s teams. The Rams’ high representation of women in the coaching ranks is a testament to their proactive approach to hiring, which starts with building a diverse, quality candidate pool. Some of Walker’s tactics:

1. Go beyond posting the position on your website and the usual job boards. Advertise for the job in the local newspaper, on social media and among your alumni base to reach different audiences.

2. Consider your competition. Look at schools that recently hired a coach and ask about the other finalists for the job. Always keep an eye out for quality coaches of the teams you play, too — they could end up on your short list.

3. Reach out to women who could be a good fit. As Sheryl Sandberg points out in her best-selling book “Lean In,” research shows women often apply for a job only if they meet 100 percent of listed criteria, while men will apply if they meet 60 percent. Urge quality female candidates to apply, and you may find that a little encouragement goes a long way.

Among the most-discussed factors at Bjornsrud’s round table and at conferences nationwide? The quest for some semblance of a work-life balance in the high-scrutiny, travel-heavy, around-the-clock world of coaching. It’s enough to burn anyone out, male or female. But for mothers who coach, the exhaustion, stress and, often, guilt tied to the job intensifies. “I know a lot of women who have gotten out of coaching because they want more family time,” says Arizona State University women’s basketball coach Charli Turner Thorne. “And I have players who never considered coaching because they didn’t see them being able to have everything they wanted with their family life.”

A quieter culprit of dissatisfaction bubbles beneath gender-related microaggressions that some women say are rarely acknowledged. A 2016 Women’s Sports Foundation study revealed many female college coaches perceived gender bias in career advancement, influence within an athletics department and access to resources, among other areas. About 80 percent of women who responded to the survey believed it was easier for a man in their field to get a top-level job, and 91 percent thought it was easier for men to negotiate salary increases. Forty percent of the female coaches surveyed felt they were discriminated against because of their gender, compared with 28 percent of the male coaches.

“It’s easy to call overt sexism ‘sexism,’” says Laura Burton, a professor at the University of Connecticut who studies gender issues in sports. “It’s so much more difficult when it becomes more subtle and more implicit. It’s harder to name it, and it’s harder to see it and put our finger on it.”

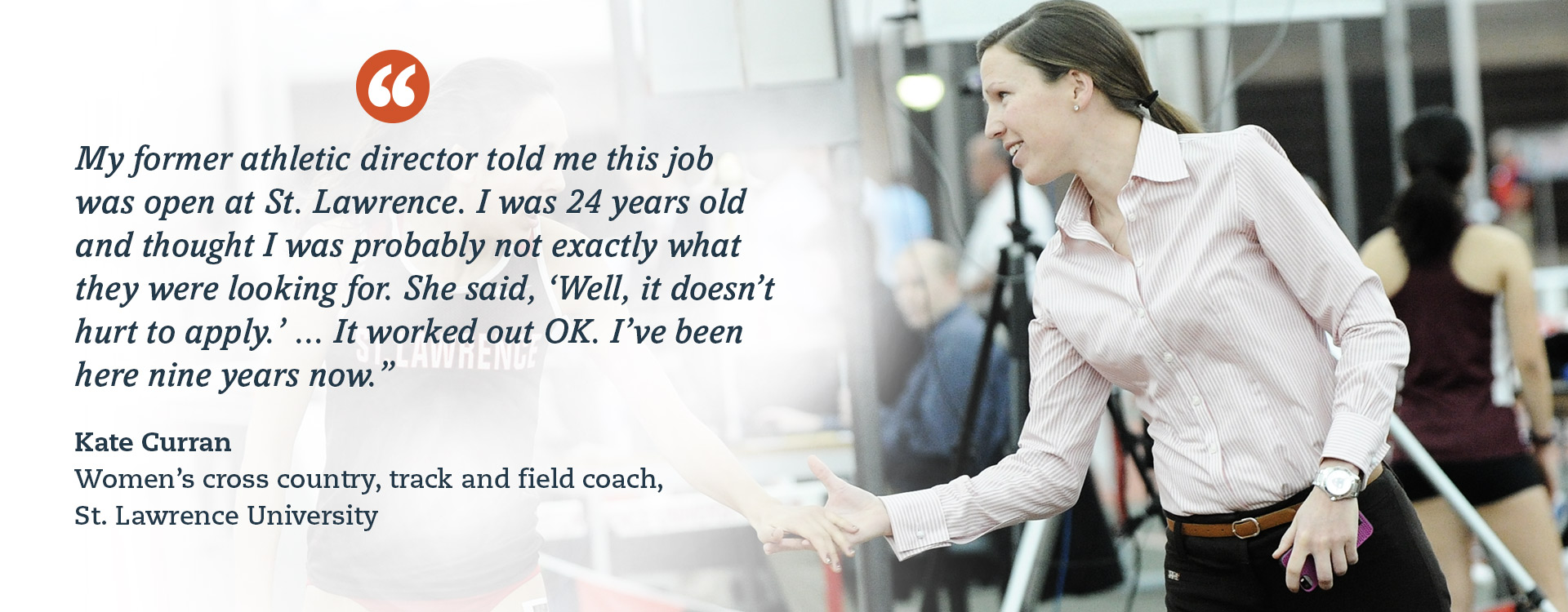

Tara Freeman / St. Lawrence University

The NCAA office of inclusion offers the following list of best practices for schools to discourage discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning people:

1. Establish nondiscrimination policies. Have a written nondiscrimination policy that explicitly covers “sexual orientation,” “gender identity” and “gender expression.”

2. Have LGBTQ-inclusive codes of conduct. Ban anti-LGBTQ conduct by players, coaches, athletics administrators and fans. Teams should be encouraged to create their own codes of conduct outlining consequences for engaging in homophobic and transphobic behaviors.

3. Use inclusive language in department communications. Ensure all media communications and recruiting materials (media guides, community outreach, team camp brochures, etc.) include a nondiscrimination clause and use LGBTQ-inclusive language.

4. Provide accessible resources. Maintain up-to-date LGBTQ inclusion resources that are readily available to coaches, players and staff throughout the year.

5. Hold annual LGBTQ inclusion trainings for staff and students. Hold timely mandatory training sessions that review policies and codes of conduct, as this is essential to creating LGBTQ-inclusive environments.

More information here

Despite the challenges, some athletics administrators have shown a commitment to gender equity among their coaching ranks. Tonia Walker leads a staff at Winston-Salem State University with female coaches at the helm of every one of the school’s women’s teams — a feat she ties to a proactive approach to hiring and a family-first atmosphere. “Women are often overlooked,” Walker says. “If they can bring quality, if they can bring purpose, if they can bring talent to the position, why not give them the opportunity?”

In 2007, Sherri Murrell was the only openly gay coach in women’s basketball. A decade later, the list of publicly out coaches in the sport remains just as small. Advocates including Murrell point to a persisting climate of fear that deters female coaches from coming out.

More and more, concerted efforts to move the needle are emerging. In 2015, the NCAA’s Gender Equity Task Force reconvened after a 22-year dormancy to stimulate new conversation around Title IX. Last fall, presidents at NCAA schools were invited to sign a pledge to address the low representation of women and racial and ethnic minorities in athletics leadership roles. (More than 60 percent have signed as of mid-December.) And Division I conferences are partnering with the Alliance of Women Coaches to host leadership forums specifically for their female coaches.

Advocates say efforts to make the coaching world a better place for women also will help men, who are not immune to their own struggles with time demands and family matters. “What’s good for women is good for everybody,” LaVoi says. “I think there are a lot of men who are standing on the sidelines thinking the same things but can’t speak up.”

“I affectionately call our program the recycling bin. We try to be a program that lets women get their confidence back. … We bring women in, hire them as assistant coaches and help them get back in it.”

For Hutchins, speaking up has never been an issue. When she was the captain of the Michigan State University women’s basketball team in 1979, she led her team in suing the university for Title IX violations – and won. Decades later, the coach continues to challenge the status quo with the confidence of a woman who has made it to the top and the passion of a woman who has spent a career fighting these battles. “We’ve come so far,” Hutchins says. “But that doesn’t mean we’re equitable. We have to remain vigilant.”

That’s why, every season, Hutchins approaches her softball program with a mission that stretches beyond winning games. She teaches her team about Title IX, shedding historical perspective on young women who enjoy opportunities Hutchins never had at their age. She runs practices with a fire in her stare — that same intensity she witnessed in her own mentors — and demands her players uncover the strength that she knows lives within them. She is molding a new generation of leaders — in sports and out — and she doesn’t take the responsibility lightly. “Ultimately,” she says, “we’re trying to make the world a better place to be a woman.”